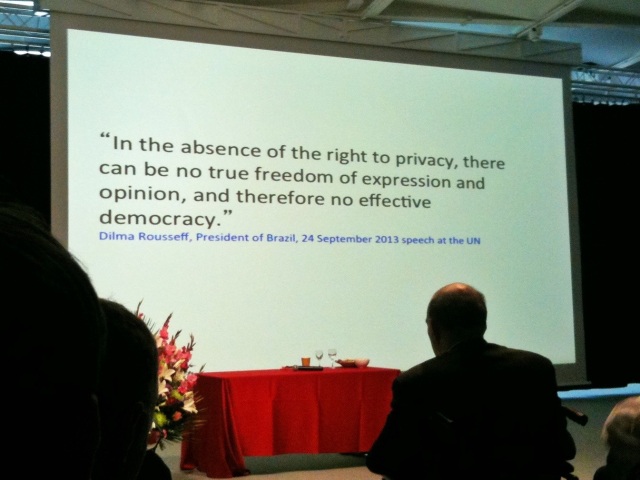

I went to the Congress on Privacy and Surveillance at the EPFL last week. The day-long conference was a rare opportunity to listen to some of the most renowned technical and legal experts in the field.

When Pamela Jones closed up shop at Groklaw in August, I was shaken.

There is now no shield from forced exposure. Nothing in that parenthetical thought list is terrorism-related, but no one can feel protected enough from forced exposure any more to say anything the least bit like that to anyone in an email, particularly from the US out or to the US in, but really anywhere. You don’t expect a stranger to read your private communications to a friend. And once you know they can, what is there to say? Constricted and distracted. That’s it exactly. That’s how I feel.

Or as Bruce Schneier put it, the whole world is starting to feel like being at a giant airport security gate: no jokes allowed.

I’ve been joking for years in emails and phone calls to my friends in the States. “Hello Echelon guys” we used to say, especially if we were talking about our travels or how we felt about current events, things we thought might interest them.

Then, little by little, I noticed that I was censoring myself. There were subjects I stopped talking about in emails, to avoid using what I thought might be “trigger words.” Later, I realized I was doing this on Twitter and in my blogging too. I’m just a normal person, talking about normal things people talk about, but I was choosing my words carefully and making a conscious decision not to write about certain things.

Since last June, none of this seems so paranoid anymore. I find the idea that authorities may be listening to everything I say to my friends and family unsettling.

I think I was hoping to find some relief for this discomfort at the EPFL Congress.

The event was chaired by Professor Arjen Lenstra, and it was well-organized. Even with more than 800 registered attendees, there was little waiting during registration or during the breaks. The speakers were all excellent and recognized experts in their fields. Appropriately, none of the attendees had name tags. Instead we got conference buttons.

However the names and email addresses of everyone who registered were available through the EPFL smartphone app. I couldn’t decide if this was just normal conference practice or an oversight. I don’t remember having been told my email adress would be available to everyone.

The schedule was organized so that most of the legal presentations were in the morning. I found the technical talks in the afternoon a bit more stimulating, but all the speakers were good. No boring presentations here. Interestingly, most of the afternoon presentations were made without slide support. Several people commented on how captivating these presentations were, even with (or perhaps because of) the lack of visual support.

I was pleased to discover how entertaining Bruce Schneier is after reading him for so many years. I noted that he too mentioned self-censorship because of his knowledge that he is likely to be considered a “target.” He didn’t say by whom. He argued eloquently for transparency and cost/benefit analyses on government surveillance programs. Later in the afternoon, Bill Binney received a standing ovation for his account of the years he spent at NSA and his whistle-blowing activities.

Nikolaus Forgó discussed the difficulty of determining what is actually meant by the term “personal data.” Throughout the day, the speakers called attention to the importance of consent with respect to the capture, storage and use of such data, either by authorities or private enterprises. Several speakers mentioned that most people don’t pay attention to and/or aren’t aware of how their data may be used. Consent is often therefore given without thought to the consequences. Furthermore, in the online world, since consent is almost always required as a condition of using services that people can reasonably be expected to use (i.e. not using the services would place a person at a disadvantage or would isolate him from family, friends and colleagues), de facto this choice isn’t a real one.

The assumption seemed to be that if people were better informed they would demand a legal framework that guaranteed their right to privacy and prohibited mass surveillance on the part of any entity.

I think it is important to distinguish between government and business use when considering public sentiment regarding privacy of personal data, although in practice the lines are often blurred since data collected by businesses may be shared wittingly or unwittingly with authorities, and it is exactly this situation that is the object of current revelations related to mass government surveillance.

Still, I think people may have different expectations regarding business or government use, a distinction that none of the speakers explicitly addressed. The conflicting expectations of citizens might be: protection from use of personal information for purposes other than intended on the part of businesses, and an expectation of data security in order that this data may not fall into unscrupulous hands. On the government side, citizens will want freedom from constant surveillance, but they also likely want authorities to protect them from harm. In other words, they want governments to protect their liberties, not just in terms of freedom of speech or freedom of religion but also in terms of their physical person by making their environment safe.

Someone who is afraid to go outside for fear of their personal safety is just as much a prisoner as someone who lacks the freedom of self-expression.

The reality of these expectations is also certainly highly dependent on where a person finds him or herself. The concerns of upper class Europeans or North Americans of European descent are likely to be quite different from those of political dissidents in China or peaceful protesters in northern Africa. Unfortunately, despite the large diversity of nationalities in the audience, the Congress was almost exclusively focused on recent events in Europe and the United States.

Dictatorial regimes of all political flavors have used surveillance to keep citizens under control. I can’t help but think of The Lives of Others. During the cold war, the US got a lot of mileage out of portraying the communist block as a surveillance state. So how can this kind of surveillance suddenly be ok? Can any such system entrusted to men be truly safe from abuse of the enormous power it offers? Do the rewards justify the risk? Do they justify the price we have to pay?

Times change.

Over the last few weeks I’ve spoken with quite a few people who are concerned by mass surveillance and deplore the lack of transparency but who ultimately see it either as inevitable or as the lesser of evils. In fact, among folks I’ve spoken with, most of them well-educated middle class Europeans, this seems to be the most predominate view. As one person from northern Africa put it, there are crazy people who will take every liberty you give them and use it to carry out their extreme agenda. Shouldn’t we rather make life more difficult for them, even if it means giving up a little privacy?

This, I think, is the heart of the matter. Is there a way we can protect our privacy without blinding those who would treat our information honestly and conscientiously to preserve the public welfare? (Do such people even exist?) I was hoping for an ethical or philosophical debate at the Congress, but none of the speakers seemed to acknowledge any positive benefits of mining such data; they only spoke of the dangers of losing our privacy. Perhaps this was a deliberate choice on the part of activists who feel that there is no need to defend the benefits of what they see as the status quo. Indeed many of those benefits could still be achieved with anonymized data, but there was no discussion of this point at all.

Ironically, the debate has already started elsewhere. For example, I noticed this article just a few days ago. The arguments there seem consistent with the views I’ve heard expressed in my own conversations. I would have liked to have seen a debate about it at the Congress.

“Privacy protects us from people in power,” Bruce Schneier said. He went on to say that the next challenge is to design systems we can trust. Jacob Applebaum said something similar, telling us that he believed encryption was the answer. He said we need to design systems that will protect our privacy by default, but as someone said in during one of the Question and Answer sessions (I don’t remember which one), allowing mass surveillance while saying that we need to use encryption to protect our privacy is like giving out guns and then saying we need to wear bullet-proof vests to avoid getting shot.

I’m not sure the people I spoke with would fully agree with that. Most of them seem to expect authorities to be able to use such data if necessary to protect citizens. Can these competing objectives be reconciled?

I think few people realize that the question of privacy is only the beginning. Ultimately what is at stake is the access to technology itself. I listened to an interesting talk by Cory Doctorow on this subject some time ago. He’s far ahead of most in thinking that the issues at the root of conflicts related to copyright and illegal file sharing have broader implications. As technology becomes more powerful and accessible to the masses, the risk of its misuse for unspeakable actions becomes greater. All types of technology from biotech to sensor systems to production equipment and robotics could be used in nefarious ways. UAVs are already subject to special laws in many places. 3D printers may fall under similar regulations. In some countries, even things we take for granted like cameras and GPS units are strictly controlled. However as the technology becomes acessible to people who want to make their own devices, how long will it be before someone thinks it’s a good idea to put a stop to such activities? No one brought this up at the Congress. Jacob Appelbaum came the closest when he mentioned the difficulty of running diagnostics on personal computing devices to check the integrity of the BIOS. How can we protect both our devices and our access to use them? What advantages and disadvantages will this bring?

The right to privacy and the right to have access to and use technology are related and pose two of the most fundamental societal questions for the coming decades. The way people think about these questions is shaped by both their physical situation and cultural beliefs and norms. We live in a world where those used to “benevolent” governments often take for granted a certain state of affairs, but what is needed is a rising awareness of the benefits and consequences of these decisions on a broader scale. We need scientists, philosophers, historians, anthropologists and legal scholars (and maybe a few science fiction writers) to help us think through these issues, and we need to step back and ask if the model we use to assess the questions of what is right and what is wrong is still appropriate in an increasingly technological world.

Further Reading

The Coming War on General Purpose Computation

The Sky Is Not Falling, It’s Fallen

Privacy and Surveillance: Jacob Applebaum, Caspar Bowden and More